There was a particular kind of freedom that came with being seventeen in the early 1990s, a freedom measured in cubic centimetres and held together by optimism, cable ties and a pair of L plates. One-two-five. Even now, saying it out loud feels like opening a door.

Back then, 125cc bikes were not something you rushed through on the way to a “proper” bike. They were the whole point. You would see them everywhere: groups of riders spilling out of housing estates, gathering at petrol stations, fanning out across country lanes. Two-stroke smoke hung in the air behind us, that sweet, oily smell drifting through towns and villages long after the sound had gone. You did not need to see the bikes to know they had been there.

The bikes themselves were a big part of the magic.

If someone turned up on an Aprilia RS125 Extrema, it stopped conversations. With its GP-inspired bodywork and razor-sharp looks, it felt as close to a race bike as you could get on L plates. Once de-restricted, it was genuinely quick for its size and weight, and it demanded to be ridden properly.

The Yamaha TZR125 was everywhere for a reason. It was sporty, loud, and just within reach for a lot of young riders in the UK. It looked right, sounded right, and revved hard enough to make every short straight feel important.

Honda’s NSR125 had a different appeal. Angular, sharp-edged and unmistakably of its era, it combined performance with a reputation for reliability that made it popular with riders and parents alike. It was the sensible choice that never felt boring.

Then there were the bikes that refused to stay on the road. The Kawasaki KMX125 and Suzuki TS125, a couple of learner legal trail bikes, they were two-stroke all-rounders of the era. They would commute, carve back roads, then happily cut across a field or disappear down a muddy track because someone swore there was a shortcut.

If style mattered most, the Cagiva Mito 125 stood apart. With looks clearly inspired by Ducati’s 916, it was dramatic, compact and unapologetically impractical. You did not just ride a Mito, you made a statement every time you stopped at the lights, where drivers who were not in the know, though you were riding a proper sports bike.

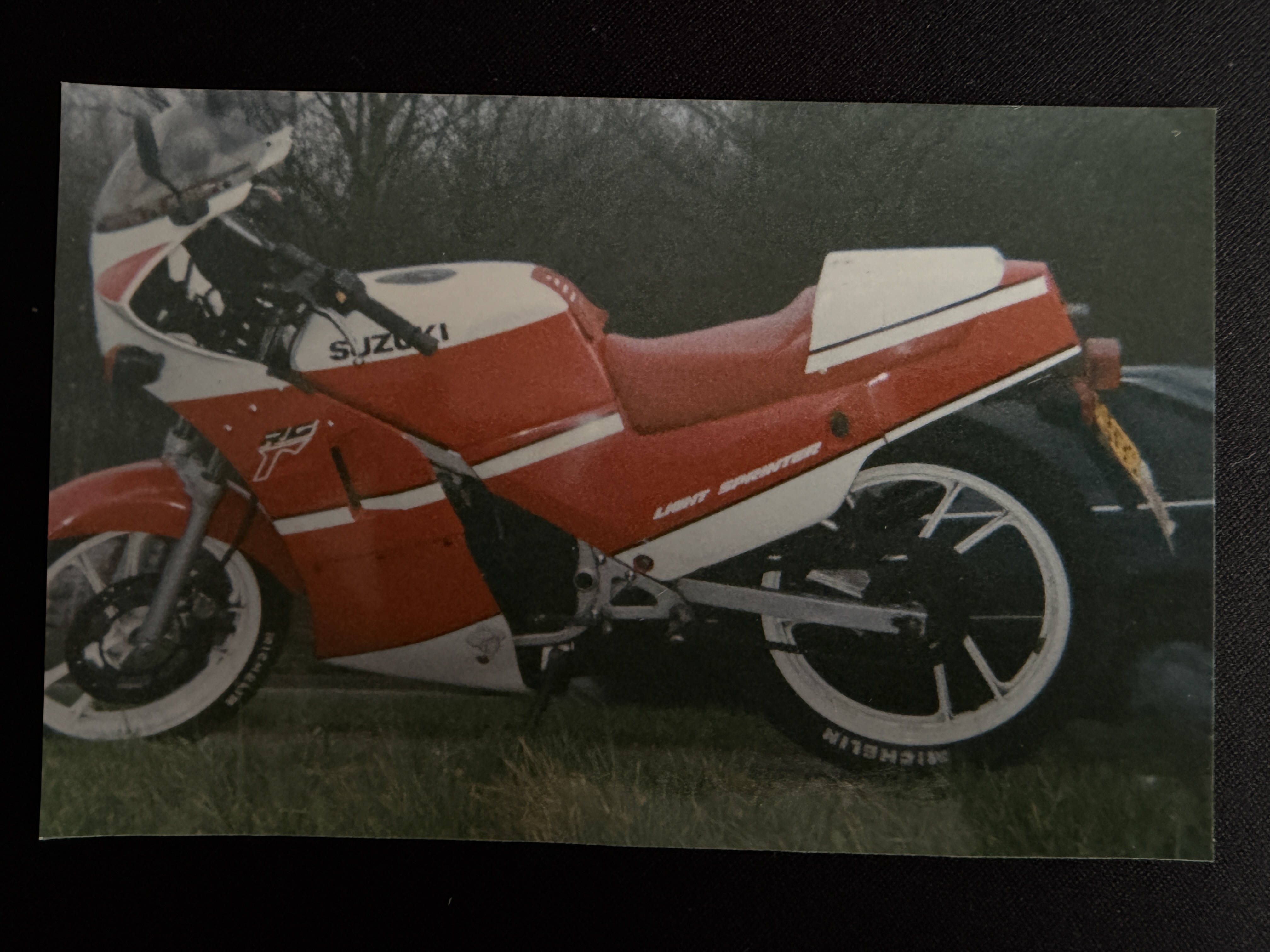

Then the bike I had, the Suzuki RG125 Gamma completed the picture. High-revving and great fun for such a little bike, it rewarded commitment and punished laziness. Keep the revs up and it felt far quicker than its capacity suggested.

What all these bikes shared was the character of a proper two-stroke. Light weight, sharp throttle response. Whilst standard bikes were around 12BHP, fettling with exhaust, filters and sprocket sizes allowed us to tweak those power figures and top end speed. However, when fully unrestricted, you were up to 20+ bhp on certain bikes. That may not sound much now, but on a small, light machine it was enough to make them feel pretty fast. They were capable of motorway speeds – albeit not allowed on motorways with L-plates, so at least they were happy on faster A-roads.

Every now and again, someone would turn up with a Stan Stevens tune. You could usually hear it before you saw it, crisper on the throttle and cleaner through the revs. When the road opened up, they would simply pull away, leaving the rest of the group chasing a shrinking dot in the distance. Admiration, jealousy and endless arguments followed about whether it was worth the money and how long the engine would last.

Of course, these bikes were used in all weathers and worked hard, so they all demanded ongoing attention and mechanical sympathy. Fixing the bike was on you though, the cost of a dealer service was way outside of your budget.

In fact, money was always tight at 17, but it rarely stopped us. A handful of loose change would put fuel in the tank, and on a 125 that could last most of the day. Filling up felt like a small victory. Full tank, nowhere specific to be, and hours of daylight ahead.

Race replicas, trail bikes and battered commuters all mixed together. If it ran, it belonged. There was a sense of camaraderie that feels rarer now. No phones, no group chats, just knowing where people would gather. Outside the chippy. At the petrol station. Down the shops.

Unfortunately, you do not see the youth of today adopting L-plated 125s anymore. There’s no smell two-stroke smoke drifting through the air on a summer evening. Riding feels more solitary now, more structured, shaped by grown up rules and life pressures. However, back in the early 1990s every ride felt like an adventure because everything was still new. The bike, the road, and your place in it all. A 125 did more than take you places, it gave you freedom in its purest form. Fuelled with spare change, ridden with friends, and remembered long after the bikes themselves were gone.

Oh how I loved that era.

Finally, I make no apologies for my long hair in the above photo…remember it was the 1990s!

Leave a comment